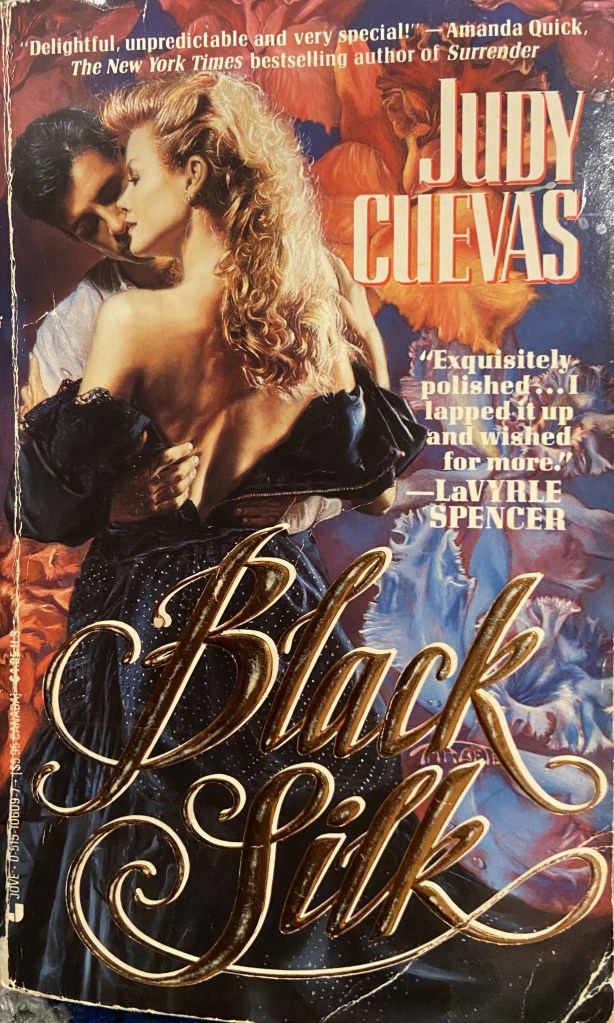

revisiting Morrow Fields (over and again) on a hot summer day or: eroticism and the tangibility of the body in Judith Ivory’s Black Silk

spoilers for Black Silk by Judith Ivory throughout

Last week I was at a bus stop, it was 90 degrees Fahrenheit outside and I had walked a lot that day; I was wearing sandals that are not ideal for extended periods of walking (although I love them) so the sixteen remaining blocks to reach home seemed like a dreadfully long way. It felt so good to sit down on a bench, to rest my feet and back. However, after waiting several minutes I checked my phone and read the bus was running behind. Even though I had been sitting for several minutes I was sweating from the heat and the lack of breeze; waiting no longer seemed so restful – walking home would get me to air conditioning faster. I stood up and started my walk.

Last year, Connor Lightbody wrote about the increase of body sweat depicted in film for his article 2024: Making Movies Sweat Again:

Since the turn of the millennium, and what can possibly be attributed to the rise of the Disney conglomerate and a sense of literal sanitation, there has been a distinct disappearance of perspiring people on the silver screen. The filmmakers of 2024 seem to be turning that funky tide with the likes of Hoard, Monkey Man and Love Lies Bleeding, while Josh O’Connor glistens on centre stage with sweaty turns in both La Chimera and Challengers.

Naturally, this made me think of Black Silk and the scenes set at Morrow Fields.1 I was thinking specifically of Judith Ivory’s ability to capture the complex desire between two people, in Victorian England, outside on a hot day, in close proximity to one another (physically, spiritually); the heat and sweat of budding attraction constricted by damp fabrics clinging to warm skin, “[Graham] grimaced again, then ran his hand back over his head, as if to say it was hot standing out in the middle of the sun. He did look hot. A velvet vest was heavy for summer. His coat was dark.” Simultaneously, Submit is perspiring through her clothing – sweat visibly stains the armpits and torso of her dress. Her involuntary reaction to sweat dripping beneath her heavy clothing adds to the eroticized moment:

Then she made a quick, unself-monitored gesture. She pressed her dress between her breasts – the black dress looked finally hot. Perspiration showed wet under her arms, ran a path down the bodice. Graham felt sexual interest ripple over him warmly to settle in his groin. He felt the first mild lift.

Previously, I wrote about the liminality of Morrow Fields, the posting house where Submit is staying while her dead husband’s will works its way through probate. Graham visits her at this boarding house, where she is the only guest, on his way to and from Netham, his estate. Their interactions at Morrow Fields start somewhat informally with a pretense of politeness; they usually end after a swerve into sweaty, sexually charged moments:

“You are devastating,” he said honestly. Her skin, he realized, was flawlessly smooth, something a man wanted to touch. What she was was tactile. She had a fine, gold down along her cheek. He watched her mouth waiting for it to open, thinking of the teeth that overlapped in front. He ran his tongue along the back of his own.

While at Morrow Fields, Graham twice attempts to kiss Submit; she pushes away from both advances. The transience of Morrow Fields prevents them from exploring their growing attraction, at least literally; but I think the sweating and removing or loosening of clothing hints at a symbolic sexual release, “He slipped off his coat and began to unbutton his vest. A breeze flapped his shirt against his body, flipped his vest open to the lining. He flung his coat over a shoulder and looked around. They had come a long way.”

In his article, Lightbody goes on to say, “The common adage surrounding Challengers, and it is a prominent metaphor within the text itself, is that everything is tennis, except tennis, which is sex. So it stands to reason that each exuberant, high-octane tennis match that occurs between O’Connor’s Patrick Zweig and Mike Faist’s Art Donaldson is laden with sweat: they’re fucking.”2

Submit and Graham have sex for the first time at Netham – on a staircase. This scene is (somewhat) mirrored later on at Motmarche, after Graham has inherited the estate – something no one, expect perhaps Henry, anticipated.

Of note: staircases, stairwells, or stairways are transitory spaces, regardless of how ornately (or custom) they may be decorated. Their purpose is to connect one floor to another; people may pass through them to go from one space to another, but they do not “stay” in them. What is important about these staircases, where Graham and Submit initiate sex, is that they are affixed within the homes where Graham and/or Submit (and/or Henry, it always comes back to Henry), have dwelled. Graham may follow the group during a season, moving from home to home, party to party, but Netham, like Motmarche, awaits, a place of eventual return.

For her Substack, Emmy Potter also wrote about sweat in cinema,3

Too many movies today feel more like pharmaceutical ads where everyone looks perfect and happy because all their problems—including finding consistent air conditioning during the blazing hot summer—either don’t exist or have been solved. If a character is supposed to be dirty, or god forbid, *SWEATY*, it no longer looks like they’ve done any effort to achieve it. The dirt and sweat look more like they’re just another step of a mindless “Get Ready With Me” routine video on social media; applied to the fully made-up glamourous face and body like you would a serum or lotion. Everyone is supposed to look pretty first and everything else that makes you interesting and human second.

I think some authors and readers of romance will say the genre is the place where the body4 exists to freely enjoy pleasure. I agree, partially! I am drawn to writing that is interested in exploring bodies holistically – capable of enjoying pleasure but also where pain or discomfort is acknowledged. The latter is not always examined to its full penitential in romance for reasons that I find boring.5

Last week I read a romance that might be the worst book I’ve read all year. 6 The book kept insisting that it was sexy in the least sexiest ways possible, that it was saying something about pleasure and the body . . . but it was mostly weird about genitals, labor, and intimacy. I’m being vague because I might write more about the book later but, then again, maybe not because I do not want to re-read any parts of it.

I think great art has the potential to connect you to your body – from the beautiful to the grotesque – to question the existence of arbitrary limits, to move you in uncomfortable ways. Potter further writes, “sweating is not pretty (no matter how hard the 1980s tried to make you believe that). Sweating is proof of a life lived, a body working, an emotion being felt.”

As I made my way home, I began to feel a sore that had developed on the side of my foot from the cute, but impractical, sandals I was wearing, the knee I injured in high school during hockey practice was now aching and stiff, I was slouching (a decades-long habit formed before my breast reduction surgery), and I could feel sweat dripping down my back. I was uncomfortable yet I was connected to and aware of my body.

About five minutes after I started walking home, the bus drove past me.

- yes again, more like always! ↩︎

- addendum: Black Silk includes a gloriously sweaty tennis scene between Graham and a much-younger man. I can’t believe I didn’t think to include it in this post! my only excuse is that I’m always thinking about Submit and Graham sweating. ↩︎

- Potter cites the important text of our time, RS Benedict’s Everyone is Beautiful and No One is Horny. When I re-read Benedict’s piece, this passage stood out to me, “A body is no longer a holistic system. It is not the vehicle through which we experience joy and pleasure during our brief time in the land of the living. It is not a home to live in and be happy.” ↩︎

- usually meaning a female body, which I don’t have the energy to explain why this is a harmful and alienating assumption. ↩︎

- “it’s supposed to be a fantasy and there can be no bad feelings in a fantasy,” get real! ↩︎

- When the Marquess Needed Me by Lydia Lloyd, 2025. ↩︎