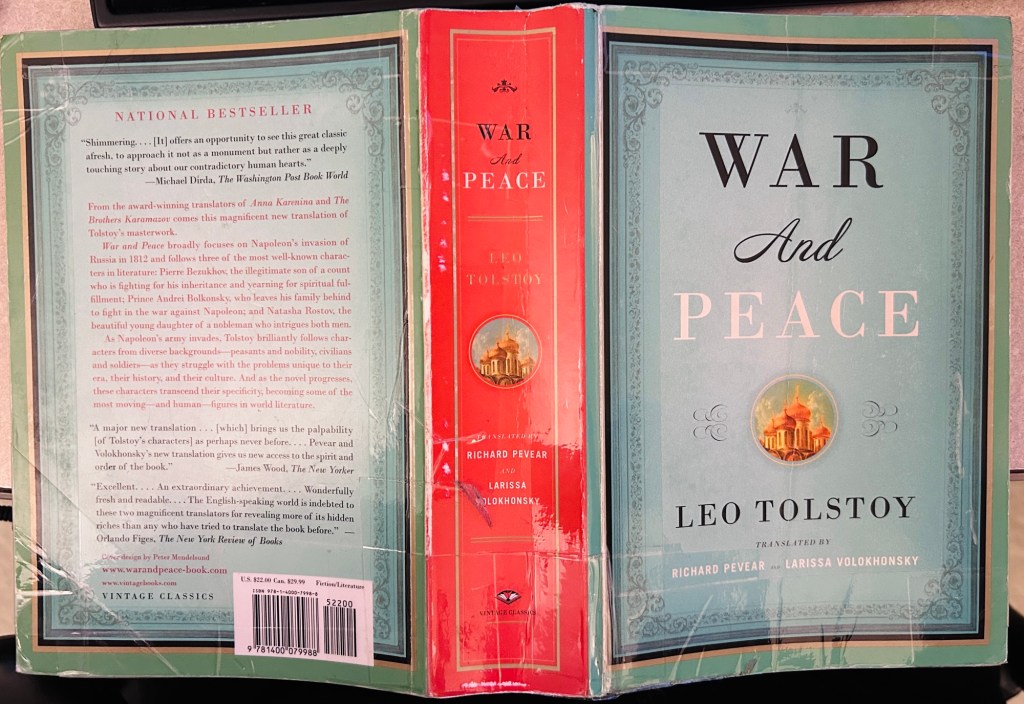

my copy of War and Peace is the 2008 First Vintage Classics Edition, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. This edition is divided into four volumes and a two-part epilogue. This post is about events from Volume II.1

Volume II begins in 1806, Moscow; Nikolai Rostov and Vassily Denisov are on leave from the military. They visit the Rostov family home, everyone is excited to see Nikolai home. Natasha has grown into a beautiful young woman. Sonya, the young woman Nikolai promised himself to before leaving for war, hides; the status of their relationship is unclear.

Pierre Bezukhov, now married to Hélène, learns from an anonymous letter that she is having an affair with Fyodor Dolokhov who opening taunts him in front of others. In his anger, Pierre challenges Dolokhov to a duel. Pierre, surprisingly, injures Dolokhov. Hélène denies the affair but Pierre embarrassed and upset leaves her.

It was reported that Prince Andrei Bolkonsky was lost during the battle of Austerlitz. His family, however, has held onto hope that he may have survived in part because of Andrei’s wife, Lise (also referred to as the little princess), who is pregnant with their first child. Andrei arrives home in time for the birth of his son and to be with his wife as she dies from childbirth.

Nikolai introduces Dolokhov to his family who all like him except for Natasha who finds him to be calculating and notices he has taken an interest in Sonya – who is still very much in love with Nikolai. Dolokhov proposes to Sonya and she refuses him, her reason is that she loves another.

After Sonya refuses his proposal, Dolokhov ropes Nikolai into a card game. Nikolai eventually loses 43,000 ruples; he goes home and sees his family in their drawing room. He considers suicide but he hears Natasha’s singing voice and takes notice of how it’s changed since she began taking lessons. He begins singing with her after she is able to hit a difficult B in the song,

“All this misfortune, and money, and Dolokhov, and spite, and honor – it’s all nonsense . . . and here is – the real thing . . . Ah, Natasha, ah, darling! ah, dearest! . . . How is she going to take this B . . . She did it? Thank God!” And without noticing it, he himself was singing, so as to strengthen that B, taking the second voice a third below the high note. “My God! how beautiful! Did I sing that? What happiness!” he thought.

After Pierre leaves Hélène, he experiences a spiritual awakening after meeting a Freemason. He tells the man he hates his life. The man advises Pierre to think about his life and what he would like it to be like.

The teachings inspire Pierre to live a life devoted to good works. This includes reforming how his land is managed . . . however his estate agent sees that these reforms are not enacted,

The steward promised to put all his powers to use in fulfilling the count’s will, clearly understanding that the count not only would never be able to check on whether all the measures had been taken for selling the woodlands and estates, so as to pay off the Council, but would probably never ask and never find out that the buildings constructed were standing empty and that the peasants went on giving in work and money all that peasants gave other masters – that is, all they could.

Inspired by his personal experience of how communications breakdown during battle, Andrei begins a project to help prevent repeating mistakes that can lead to significant loss of soldiers.

Andrei’s young son, Nikolai Bolkonsky, has been ill since birth. Doctors and nurses have struggled to treat the illness. One night, Andrei checks on the young Nikolai and believes he has died however the child’s fever has broken and is finally on the mend. His sister, Princess Marya, and him share a moment of happiness,

They shook their fingers at each other and stood a little longer in the dim light of the canopy, as if reluctant to part with that world in which the three of them were separated from everything on earth. Prince Andrei was the first to leave the crib, his hair tangling in the muslin of the canopy. “Yes, this is the one thing left to me now,” he said with a sigh.

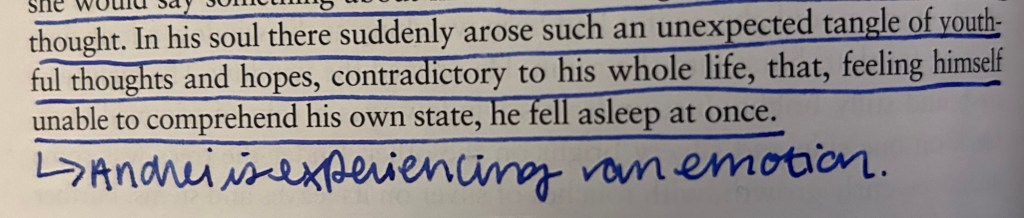

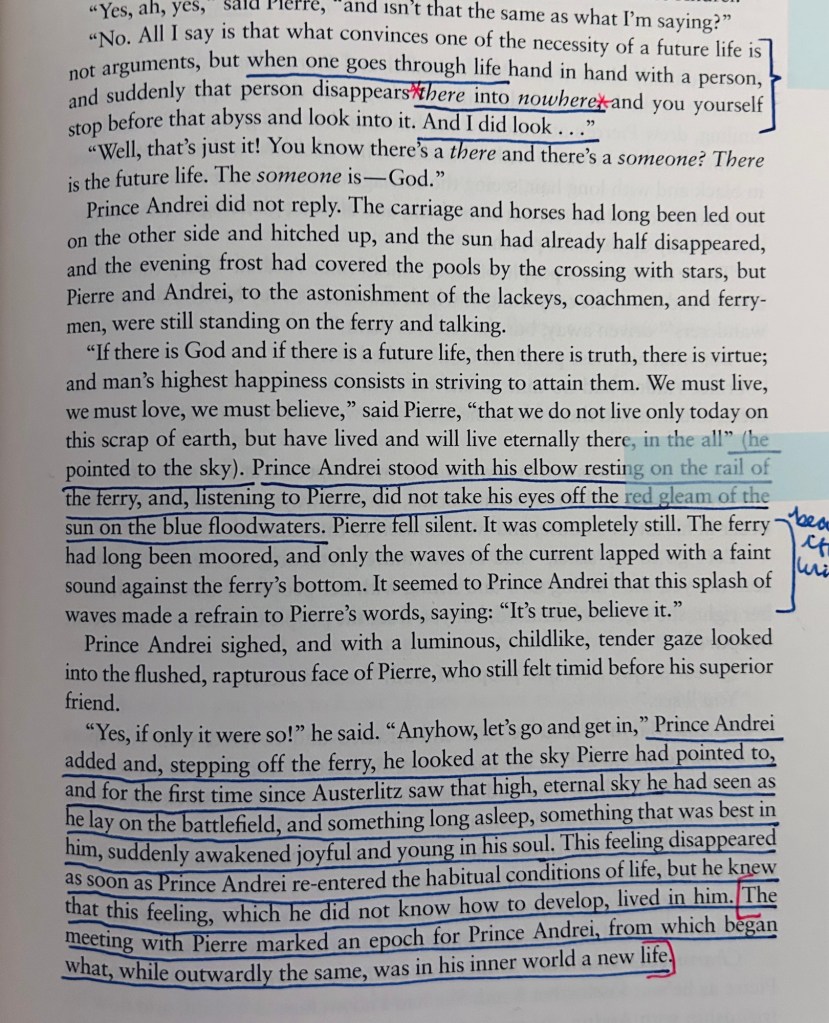

Pierre visits Andrei and the two have philosophical debates – Andrei has become nihilistic whereas Pierre is still in the early stages of his enlightenment,

“On the contrary, one must try to make one’s life as pleasant as possible. I’m alive and it’s not my fault, which means I must somehow go on living the best I can, without bothering anybody, until I die.”

“But what makes you live? With such thoughts, you’ll sit without moving, without undertaking anything . . .”

Andrei successfully adopts some of the reforms Pierre attempted to implement on his estates, “He possessed in the highest degree that practical tenacity, lacking in Pierre, which kept things in motion without any big gestures and efforts on his part.”

Natasha and Andrei meet and dance at a ball in Petersburg – they fall in love after he makes several visits to her family’s home. Andrei asks his father for permission to propose to Nathasha, but his father does not like the Rostov’s. He will only consent to the match if the couple wait one year to marry. Andrei is not happy with this requirement but accepts it; Natasha is devasted. They agree keep their engagement secret.

While in Petersburg, Andrei naïvely believes his work on military improvements will be accepted by the Emperor or the people near him. Meanwhile, Pierre has suggested changes to his fellow Freemasons,

“The entire project of the order should be based on forming people who are firm, virtuous, and bound together by unity of conviction, a conviction that consists of persecuting vice and stupidity everywhere and with all their might, and of patronizing talent and virtue: drawing worthy people up from the dust and uniting them to our brotherhood.”

Reactions to Pierre’s suggestions are not good. Defeated, he leaves the lodge for home and spends several days overcome by anguish. He records some journal entries and begins living with his wife again.

The Rostovs are still financially struggling two years after Nikolai’s massive gambling debt. They have been staying in the country to save money. Natasha and her father leave for Moscow. While in Moscow, Natasha meets Hélène and her brother Anatole at the opera. Anatole is attracted to Natasha and decides to seduce her with the help of his sister and later Dolokhov.

Natasha falls in love with Anatole and agrees to run away and elope with him – Andrei has been away for so long with little contact and his family outwardly dislikes her. Natasha writes a letter to Andrei’s sister, Marya, saying the engagement is off; her friend Sonya, prevents Natasha’s plans to run away with Anatole.

Pierre is upset that Anatole, his wife’s brother, would attempt to seduce his good friend Natasha. He tells Natasha that Anatole is already married to a young Polish woman he seduced during his time in the army. Natasha, distraught, attempts suicide. She survives but remains sick. Pierre realizes he is in love with Natasha and witnesses the Great Comet of 1812,

Almost in the middle of that sky, over Prechistensky Boulevard, stood the huge, bright comet of the year 1812-surrounded, strewn with stars on all sides, but different from them in its closeness to the earth, its white light and long, raised tail — that same comet which presaged, as they said, all sorts of horrors and the end of the world. But for Pierre this bright star with its long, luminous tail did not arouse any frightening feeling. On the contrary, Pierre, his eyes wet with tears, gazed joyful at this bright star, which, having flown with inexpressible speed through immeasurable space on its parabolic course, suddenly, like an arrow piercing the earth, seemed to have struck here its one chosen spot in the black sky and stopped, its tail raised energetically, its white light shining and playing among the countless other shimmering stars. It seemed to Pierre that this star answered fully to what was in his softened and encouraged soul, now blossoming into new life.

Often, what gives me pause are subtle changes Tolstoy makes with punctuation (brackets, parentheses, italics, etc.) or form (changing from events of fictional characters to more essays about historical events). Here are the passages from Volume II that rewired my brain.

Prince Andre and the oak tree

these chapters where Andrei begins to see Natasha as a love interest – a lot of wet, juicy, glossy descriptions of the spring foliage

before meeting Natasha and falling in love:

With its huge, gnarled, ungainly, unsymmetrically spread arms and fingers, it stood, old, angry, scornful, and ugly, amidst the smiling birches. it alone did not want to submit to the charm of spring and did not want to see either the springtime or the sun.

“Spring and love, and happiness!” the oak seemed to say. “And how is it you’re not bored with the same stupid, senseless deception! Always the same, and always a deception! There is no spring, no sun, no happiness. [ . . . ] look at me spreading my broken, flayed fingers wherever they grow – from my back, from my sides. As they’ve grown, so I stand, and I don’t believe in your hopes and deceptions.”

Prince Andrei turned several times to look at this oak as he drove through the woods, as if he expected something from it. There were flowers and grass beneath the oak as well, but it stood among them in the same way, scowling, motionless, ugly, and stubborn.

after meeting Natasha, the oak has changed! and so is Andrei changed, by love:

The whole day had been hot, there was a thunderstorm gathering some-where, but only a small cloud had sent a sprinkle over the dust of the road and the juicy leaves. The left side of the woods was dark, in the shade; the right side, wet, glossy, sparkled in the sun, barely swayed by the wind. Everything was in flower; nightingales throbbed and trilled, now near, now far.

“Yes, here, in this woods, was that oak that I agreed with,” thought Prince Andrei. “But where is it?”

he thought again, looking at the left side of the road,

and, not knowing it himself, not recognizing it, he admired the very oak he was looking for. The old oak , quite transformed, spreading out a canopy of juicy,

dark greenery, basked, barely swaying, in the rays of the evening sun. Of the gnarled fingers, the scars, the old grief and mistrust —nothing could be seen.

Juicy green leaves without branches broke through the stiff, hundred-year-old bark, and it was impossible to believe that this old fellow had produced them. “Yes, it’s the same oak,” thought Prince Andrei, and suddenly a causeless spring time feeling of joy and renewal came over him. All the best moments of his life suddenly recalled themselves to him at the same time. Austerlitz with the lofty sky, and the dead, reproachful face of his wife, and Pierre on the ferry, and a girl excited by the beauty of the night, and that night itself, and the moon—all of it suddenly recalled itself to him.

“No, life isn’t over at the age of thirty-one,” Prince Andrei suddenly decided definitively, immutably. “It’s not enough that I know all that’s in me, everyone else must know it, too: Pierre, and that girl who wanted to fly into the sky, everyone must know me, so that my life is not only for myself; so that they don’t live like that girl, independently of my life, but so that it is reflected in everyone, and they all live together with me!”

there into nowhere

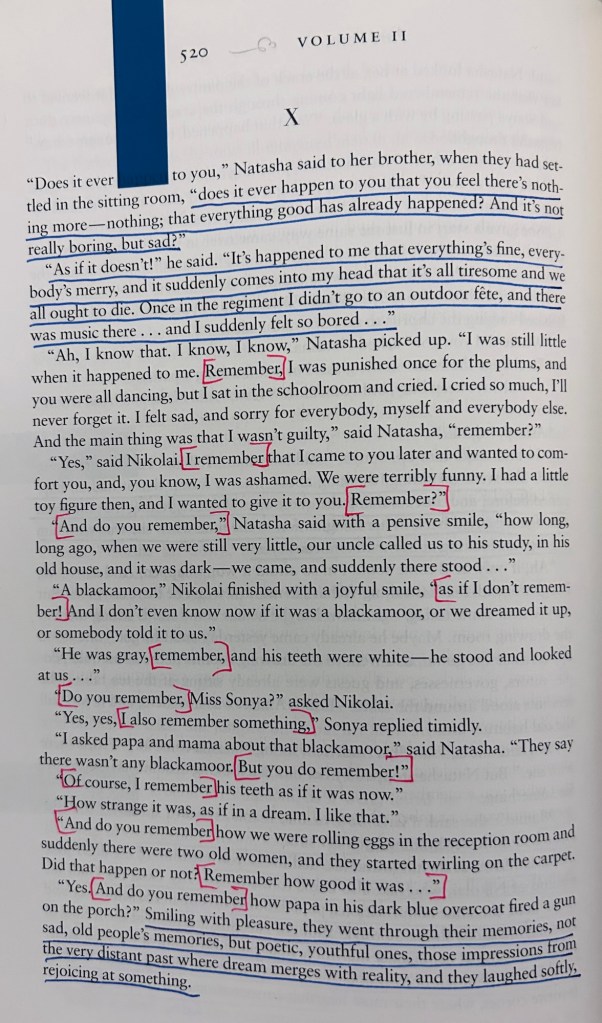

remember

Natasha went to the reception room, took her guitar, sat in a dark corner behind a little cupboard, and began to pluck at the bass strings, picking out a phrase she remembered from an opera she had heard in Petersburg with Prince Andrei. For an uninitiated listener, what came of her playing would have been something that had no meaning, but in her imagination a whole series of memories arose from these sounds. She sat behind the little cupboard, her eyes fixed on a strip of light coming from the pantry door, listened to herself, and remembered. She was in a state of remembrance (emphasis mine)

- I started Volume III earlier this month! Next W&P will include these updates. ↩︎