divorce, death (documents), liminality

spoilers throughout for Starlit Surrender and Black Silk

content warnings for: forced seduction, death during childbirth, miscarriage, uxoricide, and suicide

06/18/2025 update: I made a few punctuation edits to help with clarity

I wrote a brief companion piece, about sweat and liminality, here

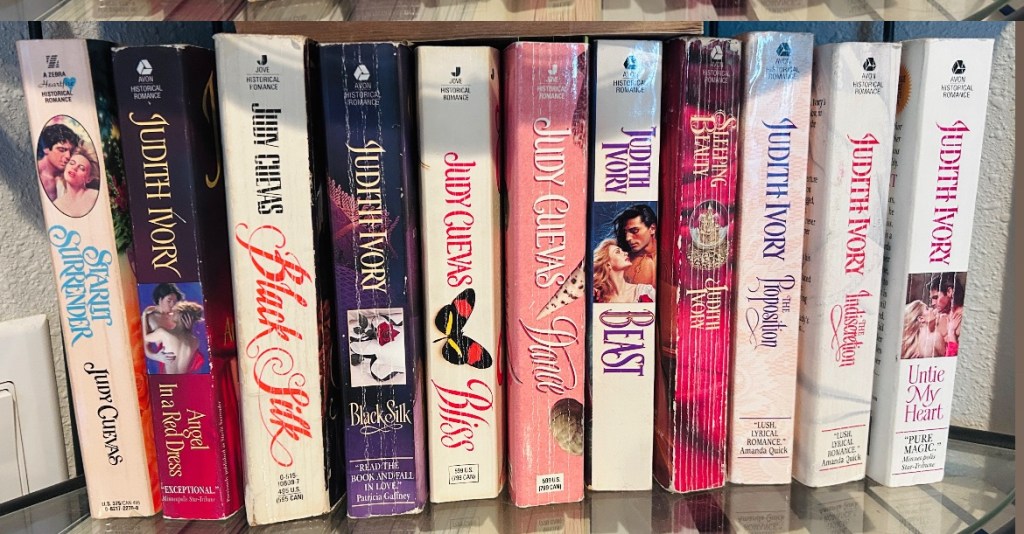

Last December I decided one of my reading goals for 2025 would be to re-read Judith Ivory/Judy Cuevas’s books in publishing order because 1. I love Judith Ivory and 2. I thought reading her books in the order they were published might give me insight into her development as a writer and the themes she explores. By genre romance standards, she has a manageable backlist comprised of nine titles. When I first read through her backlist in 2023, I was reading them as fast as I could find them and not in any meaningful order. I borrowed several from the library and bought out of print copies of Bliss and Dance from resale sites. I was obsessed!

the first reading order:

- Black Silk

- The Indiscretion

- Bliss

- Dance

- Untie My Heart

- Sleeping Beauty

- Starlit Surrender/Angel in a Red Dress

- The Proposition

- Beast

For this post, I wrote about re-reading her first two published romances: Starlit Surrender and Black Silk. With the exception of Starlit Surrender, I have avoided writing a proper review or analysis of her work.1 This author’s body of work, even when imperfect or frustrating, is so singular to me that I feel unable to make any sense of my thoughts about why I love her works or why I revisit them over and over again. These posts are my attempt at extricating the tangled thoughts that cling to the insides of my mind.

reoccurring themes: family (complicated), bureaucracy (violence) and paperwork – so much paperwork!, legitimacy, art, light, French language – French people (Catholicism), reputation, loss + grief (widows/widowers)

Starlit Surrender (1988, Zebra) – republished by Avon as Angel in a Red Dress2

setting: England and France, 1792

characters: Christina Bower and Adrien Hunt, Earl of Kewischester

The prologue is set during July, 1789. Christina and Adrien meet at a ball, they dance and flirt (more like argue, a form of flirting for this couple). Christina, a nineteen year-old, is finally making her come out; her beauty is noticed by everyone she meets. Adrien, in his late twenties, is an English earl who was raised by his grandfather in France.

The day after the ball (July 11th) Adrien sends Christina dozens and dozens of roses; he then leaves for France. After arriving in France, he spends two days journeying southeast; he is awoken on the 13th to the prelude to the French Revolution. Adrien is wounded during the revolution and barely survives getting sliced from groin to neck. Meanwhile, in England – unaware of what is happening in France – Christina’s father, upset by the roses Adrien sent and what it could mean for Christina’s reputation, encourages a match with Richard Pimm.

Chapter one time jumps three years later to 1792. Christina, now Christina Bower Pimm, is recently separated from her husband, Richard. She was unable to get pregnant and, as Richard is the son of a baronet, it is important that an heir is produced. After several failed attempts to become pregnant, Christina saw doctors and tried various methods to conceive; it was decided that her tubes were too narrow to allow an egg to pass. The marriage broken, Christina leaves her home to spend time with her cousin, Evangeline, who has set up rooms for her at the estate of a friend. The estate, of course, belongs to Adrien.3

Adrien, recovered from his injuries, has been facilitating the safe passage of French (former) aristocrats and prisoners of La Force, a prison outside of Paris, to England. French authorities – and now the English Minister of Foreign Affairs – have been searching for the source of this safe passage.

Christina and Adrien meet again while she is out riding on his land. Adrien and his henchmen were recently approached by a woman seeking aid to help move her family members; Adrien believes this woman has been employed by the administrators of La Force to lure out the source. Adrien and his men see Christina riding on his land; they chase her and she is injured during the chase, Adrien carries her back to his home.

I love this book4 and believe it is a fun place to start reading Cuevas. Everyone else will say to start with The Proposition but they are incorrect!5 By the time I got around to reading Starlit Surrender, everything here felt familiar – the movement, the language, bold character choices – the ability to render deeply intimate thoughts and feelings of her characters. From the first paragraph, Ivory’s descriptions practically levitate off the page:

The gown was extraordinary. Christina laughed deep down inside herself all the while she moved in it. How beautiful – and how very noisy – it was! Taffeta. Yard upon yard of rustling, churning taffeta, the woof and warp of different colors so that it changed and shimmered. A pale, iridescent blue that wasn’t blue but silver. Christina bounded down the terrace steps, watching it froth amongst her petticoats, delighted with the dress, the night, herself.

Adrien’s characterization amused me – he’s a rake who is, like, an actual rake.6 He is divorced, has five children with different women; when he was younger, he married his cousin,7 and while he was still pursuing the cousin, he got a servant pregnant. Later, Adrien has two children with an actress. But Adrien loves his children and even pushes back against his Christina when she refers to them as bastards:

“Why aren’t you married?” she asked quietly.

“There’s no reason to be.”

“An heir?”

“I can recognize any one of several children and have an heir.”

She blinked. “You have children?”

“They do seem to crop up now and then, in the natural course of things.”

“Bastards?”

“Not a very nice word for the little darlings, but yes. I have bastards.”

“Many?”

“Five.”

I don’t believe the text is attempting to convince the reader that Adrien is a good father (or even a good person) rather that his fatherhood is an important aspect of who he is; he likes (his) kids. Christina was unprepared for all this affection he has for his children and is insecure about her role in his life:

She was suddenly overwhelmed with the density of his life, the thirty-four years where she didn’t exist, didn’t fit in. Their one night together seemed all at once tenuous, fragile; even less significant than what she’d imagined.

When I read this the first time, it felt like a revelation. These characters are embarrassingly human.

Speaking of Christina, I think anyone who refers to her as too stupid to live can get bent!8 Christina often finds herself in circumstances outside of her control yet manages to get through these obstacles. Her ex-husband of three years, hand-picked by her title-obsessed (albeit loving) father, wanted to divorce her because she did not produce an heir and is presumed to be barren. Her hot, divorced (in England) half-French lover is being cagey about asking her to marry him because he doesn’t believe in labels (“How perfect to have such a fine woman in such a beautifully ill-defined giving relationship”). This same lover just got himself abducted by mercenaries who have faked his death, but no one believes Christina when she tries to explain this. Christina is a survivor, and, yes, I guess she can be a brat but she’s the perfect match for Adrien.

Ivory’s writing is sublime and her prose is grounded in the things that make us human: our neediness, our complicated desires, our mess (emotional and physical); Christina and Adrien track her menstrual cycle, estimate her conception date9, they use chamber pots, bodies are cut open (or shot) and bleed out, they fuck:

Blood oozed from the tip of her middle finger.

His hand wrapped around hers. Smooth, dry fingers. He took her finger into his mouth.

She was stunned.

His mouth was warm. She could feel the gentle pressure, a drawing of his teeth and tongue. It took her too long to retrieve her hand. “Sir,” she reprimanded softly. She looked away.

Adrien and Christina’s relationship is a tense, frustrating cycle of push and pull that sexually excites both (sometimes reluctantly). They argue about fucking a lot; the book has bodice-ripper elements in that there are scenes of forced seduction, and because of this, the book may not be right for every reader. I think Cuevas was experimenting here, testing the limits of power in relationships, something she continued throughout her work. In my opinion, the forced seduction scenes do not reach the violence of rape, however they can be uncomfortable (sometimes funny or hot) to read. The discomfort is the point:

What should have been ideal between them was flawed abominably by her protests. And, fair or not, he could have kicked her from France to Poland for fouling this private oasis with hypocritical statements like, “I don’t want you to touch me.” [ . . . ] His good mood curdled. He could tell by her posture, he would be dealing with her tart, priggish nature tonight. The partial erection that had accompanied him home suddenly became hesitant to accompany him inside.

“Please,” she murmured. “Please –” But she had stopped shoving against him. The classically ambiguous plea. In the context of her hands dropping back into her hair, her chin lifting up, she was no longer asking him to stop . . .

miscellany

Ivory is unparalleled wrt physicality:

He rolled her over and laid her head in his lap. He adjusted a little, scooted to make them both comfortable. Then he sat back and drank his tea while he petted her hair.

it makes me laugh:

“Christina, I am not a democrat. Not by birthright, credo, or temperament.”

kind of sweet:

While they are in France, Adrien goes to some effort to track down a book on midwifery for Christina. She is seven months pregnant and afraid of the upcoming birth. This scene actually brought to mind the scene from the film Julie & Julia when Paul finds a book of French gastronomy for Julia (it’s written in French and Julia is still learning the language).

Also kind of sweet, Adrien has wealthy boy whims:10 gardening, botany, and some light sedition. He breeds orange hybrid roses (these roses appear on the og cover of Starlit Surrener); this is tied to Christina’s fertility journey.

documents, bureaucracy, family:

Cuevas is interested in examining the ways legal documents can instantly upend – and/or simultaneously restore – the lives of her characters. Of course, these devices are not unique to her work. Historical novels have always examined the interplay between the bureaucratic processes of the past and how these systems relate to or inform our present and Cuevas is exceptionally deft at conveying this within her work.

Over the course of the book, Christina marries her first husband, separates from and eventually divorces him. She later marries Adrien.

Adrien spends most of the book refusing to marry Christina because he doesn’t believe marriage makes any sense for them. Adrien may not want to legitimize their relationship through the state, but he is dedicated to her as a partner and lover:

“Christina,” he said, “why marriage and marriage alone? Don’t you care anything for romance, affection, loving?”

“I associate those things with marriage.”

“Did your husband give you those things?”

“Don’t box me into a corner with your crazy, specious logic.”

“Is it? Just because it doesn’t lead to the prescribed conclusion? The truth is, Christina, marriage didn’t give you anything it was supposed to.” He left a pause. “But I do.”

Christina and Adrien are married by a ship captain, headed for England; Adrien needs a legitimate heir so that his title and property cannot be confiscated by the double-crossing Minister of Affairs. Their marriage announcement and Christina’s pregnancy halt the seizure of Adrien’s assets.

The ceremony took place at nine o’clock the following evening on board the English clipper, the Silver Jack. It took only ten quick minutes to make a lawyer’s daughter into a countess. Lady Christina Bower Hunt. Papers were signed. Then signed again as duplicates were prepared.

Black Silk, Jove (1991) re-released by Avon (2002)

This is the seventh time I have read Black Silk.11

England, 1858

characters: Submit Channing-Downes and Graham Wessit, earl of Netham

Graham Wessit, earl of Netham12 is the estranged ward of Henry Chaning-Downes, eleventh marquess of Motmarche. Henry and Graham had a tenuous relationship;13 and after nude drawings of Graham with an actress (there were other drawings of anonymous schoolmates) were found while he was attending Cambridge, Henry disowned him. Black Silk opens with Graham at his club, playing a game of billiards:

He stood well balanced on one foot, the other in the air. He was stretched out across the green felt, his belly flat, almost horizontal against the table’s mahogany rail. His arm was extended more than halfway up the playing surface, in a long white shirtsleeve. (He’d taken his coat off two shots ago when the balls had broken badly and the betting had doubled to above eighty pounds.) His concentration ran down the length of his arm, down the line of his cue stick, past the loose crevice he’d made of his fingertips, to the pristine white of one small ivory ball. This awkward little object, the cue ball, sat smugly at a near-unreachable angle over a clutter of irrelevant, multicolored balls. But it also sat in direct line with a red ball Graham intended to bank and sink.

A visibly pregnant young woman bursts into the club claiming Graham is the father of the twins she is carrying. He has never seen this woman before; it’s impossible he could be the father. . . Graham has the reputation of a rake14 – he is currently romantically involved with the married American, Rosalyn Schild; his cousin, William, describes him as a sybarite and “a frenetic lunatic,” even the other members of his club are under the assumption that he is responsible for getting this woman pregnant. Graham abruptly leaves the club as his friends joke and laugh at yet another scandal that Graham has found himself the center of.

Recently widowed Submit Channing-Downes is in a legal battle with her deceased husband’s illegitimate son, William. Prior to his death, the much older Henry Channing-Downes hand rewrote his will, leaving everything to his wife – his estates and title. William believes he should inherit the titles and Motmarche because, although illegitimate, he was raised in his father’s home.

Submit is forced out of her home until the matter of Henry’s will can cleared; she needs to move from one boarding house to a more affordable one situated outside of London. We are introduced to Submit while in Graham’s point of view; he sees her through a window as she is conferring with Arnold Tate, her legal counsel and Henry’s long-time friend:

She was suspended for a moment in that balletic position of raised arms. As if music had stopped for a count of three.

It felt like that many heartbeats for the man watching from the window. Graham leaned closer, fascinated, transfixed. The woman’s open arms seemed to remove status, station, even in some way her female gender. She seemed to shed everything in those moments, everything and anything limiting or superfluous to simply being human. The hint of a perfect, unself-conscious candor affected Graham, the way great beauty suddenly moves something in one’s chest; the way profound horror quakes the soul. He couldn’t decide if he was enormously attracted or almost squeamishly repelled.

Then the moment was gone. Shyly, the woman folded her arms back over a solid item she had lifted. Just as she was tucking it back against her, Graham noticed her gesture had put the black box she had been carrying into clear view. It was square, thin, the size of a box of handkerchiefs, and easily held in one hand. Then this too disappeared, lost in the shadows of the woman’s arms.

I wrote about the scenes from Black Silk that I think about all the time. I have countless highlights and notes from my readings of this book, but I think these specific scenes reveal something vital about the characters.15

morrow fields as liminal space: three scenes

An internet search for “liminal space” will bring up pictures of concrete parking garages, hotel hallways with generic wall sconces, empty shopping malls, and stairwells – each space lit by overhead fluorescent bulbs. I read this April 2021 piece from The New Yorker about liminal spaces and the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic:

Liminal spaces are in-between places that exist as means to an end, to be travelled through but not lingered in: stairwells, roads, corridors, hotels. In forcing a confrontation with these prosaic architectures of passage, liminal-space images imbue the familiar with an eerie surreality. They owe much of their appeal to their framing and lack of human presence, which obliterate context and invite the viewer to populate the image with her own memories of comparable scenes.

When I think of liminality, or liminal space, my mind goes to something metaphysical16. Like how there can be a period of time between one life event and what directly follows, or a moment in time before movement forward (or backward). . . I was thinking about the liminal spaces within a romance. The time between desire forming and the culmination of that longing; or the time between main characters meeting and falling in love.17 I was thinking about the inn at Morrow Fields!

Submit has been staying with Rosalyn at her London rental for several weeks but once Rosalyn’s season lease is up, Submit leaves to stay at a posting house outside of London.

I. chapters thirteen and fourteen (the widow/er and the box)

The inn at Morrow Fields is located about an hour from London by horseback. The inn is described as an older, run-down structure, “more coaching house than inn.” Submit is the only guest.

Graham has settled his paternity suit with the woman who has accused him of getting her pregnant; he will provide financially for her without claiming the children as his own and they will have no claim to a title. The young woman, Arabella, tells Graham her father knew him from his theater days. She lied about who got her pregnant so that her father wouldn’t be disappointed.18

Graham has sent most of his belongings and his house staff to Netham, his estate, ahead of him while the paternity settlement is wrapped up. He writes letters to Rosalyn, she sends him a periodical called The Rake of Ronmoor; Graham thinks this Rake of Ronmoor is a parody of his own life, cruelly rendered for public consumption. He has been unable to stop thinking about Submit; he rides out to Morrow fields to visit her. The ride is rejuvenating – Graham sheds the stress of the season, the gossip, the fallout from the paternity suit; he can finally relax:

As he traveled through this, somehow the muddle of his life dissolved. he began to feel almost transparent; as if, from the dome of the sky to the roots of the trees, the countryside were traveling through him, not he through it. His thoughts only flickered through him, no more sizable than the shadow and sun that filtered through leaves overhead. He moved along in the diffuse exhilaration of having a perfect, untold, unaccountable day.

When Graham arrives at the inn, Submit is not there; the proprietor tells him she’ll be back for tea. Graham walks through the dining area of the inn and notices that the tables are all, impractically, set with linen and silver for guests that do not exist (this made me think of the New Yorker piece, “stairwells, roads, corridors, hotels. In forcing a confrontation with these prosaic architectures of passage, liminal-space images imbue the familiar with an eerie surreality. They owe much of their appeal to their framing and lack of human presence.”) He wanders outside to the patio to vibrant, green grass contrasted by a blue sky. Submit is in the distance, walking closer into view:

Punctual. Punctuational, he was reminded. Today a small dot, the final period at the end of his ride; conclusive, definite.19 She grew from the poplars, a speck, a black motion separating itself from its surroundings. He waited. Surprisingly, she became not quite the same widow he had last seen. She was wearing a straw hat the color of the day, the color of her hair. And he could see, as she got closer, that the hat was banded by a deep, more striking anomaly: a ruby ribbon that fluttered and shone in the sun.

We shift into Submit’s point of view (POV),19 she realizes Graham is waiting for her. This unexpected guest disturbs her tranquil afternoon, “it was one thing to see Graham Wessit at Rosalyn Schild’s house; it was quite another to see him turn up in her own private domaine.” Submit abruptly asks Graham what he wants, he asks her if she has the box. She leaves the room to retrieve the box, she returns, to Graham’s dismay, no longer wearing the hat with the ruby ribbon. They talk about the box – Submit makes him open it in front of her, like a grown-up confronting a child. Graham surmises she doesn’t recognize that he is a subject in the drawings. He opens the box, examines the drawings:

Finely detailed ink drawings, each with its naked man and woman bonded together in some contortion. Breasts, bellies, half-open mouths. Defiant penises raised like fisted arms over the terrain and shrubbery of testes and open thighs.

Submit doesn’t understand why Henry would keep a box of pornographic images, she waits for Graham to offer some something that can make sense of this; he only offers, “We never completely know people, I suppose.” She asks him if he’s into looking at naughty pictures. Graham is floored, “he didn’t know what to say. A woman he had considered a prude was outmaneuvering him on the subject of dirty pictures.” Submit admits to getting a stir out of the pictures herself.

Graham tells her the history of the pictures, that he was expelled from school over them (and later jailed); he tells her Henry kept them as a way to deliver one final sermon to his unruly ward. They begin to argue about Henry, Graham makes a mean joke about the age gap between Submit and Henry and Submit walks away upset, “When he looked back toward the person he wanted to speak to most, she was already a third of the way to the poplars, a black, shifting dot on the vivid greensward.”20

Graham catches up to Submit and apologizes; she makes it clear that Henry’s interest in her was, “that of a husband.” Submit looks at the drawings again; she recognizes Graham’s face in them. He explains that he did the drawings because it excited him. He reveals the artist, Alfred Pandetti, member of the Royal Academy and leader of a group putting fig leaves on Greek statues, made the drawings. Henry knew this but never tried to upend the artist’s career; in fact he became a patron of Pandetti. Graham never outed Pandetti for the drawings either. Submit asks him why:

“You shouldn’t have done the pictures. Someone could still speak up. people become jealous, gain enemies. Anyone who knows might suddenly tell.”

“And I’d defend him.”

She gave him a dubious look. “By lying?”

“By focusing on a broader truth.”

“Which is?”

“His art: It’s beautiful.”

[ . . . ] Graham Wessit flirted with the dark side of human nature and, in an upside-down way, this seemed honest and brave.

Graham attempts to kiss Submit which bursts the growing tension between them. Submit tears up one of the erotic drawings of Graham with his friend, Elizabeth. This scene ends with Graham staring at her back as she walks away from him.

II. chapter twenty-one (orphans and twins)

(prior to chapter twenty-one, Arabella, the woman who sued Graham for paternity, has died by suicide leaving behind twin boys. The people investigating her death think Graham is involved somehow. He is questioned by the police about his whereabouts; Submit is brought in to back up his claims that he was with her at Morrow Fields and couldn’t be responsible for Arabella’s death. This is a humiliating experience for them both; Submit leaves the questioning in tears.)

Submit visits a nearby village and returns to the inn; Graham is waiting for her. She brusquely asks him what he is doing at Morrow Fields; he’d like her to go for a walk with him. She’s not interested, she has just returned from a walk. Graham feels bad Submit was humiliated by the questioning. He explains, “I didn’t want to expose you to the sort of prying that, by the way, I have known all my life.”

Submit is upset with Graham about letting William stay at his townhouse while Submit is homeless and alone (he did offer the townhouse to her first). They do not seem to agree about the cruelty of Henry’s will and how William deserves more than was left to him – Submit calls William an idiot and Graham says even idiots are deserving of a father’s love. They argue; Graham believes Henry understood the chaos his will would unleash, saying, “I give Henry credit. [ . . . ] Credit for riling William into a tantrum. Credit for engineering my embarrassment – and yours – over the pictures. And credit for knowing everyone well enough to predict your homelessness right now.”

We learn William’s mother was sixteen when she had him; Henry was in his thirties. Submit does not appreciate what Graham is implying by mentioning this. When she tries to leave, he tells her one of the young twins has died – he was there when it happened, “that’s all. I just wanted to tell someone – someone else who might mind.”

Submit knows the twins weren’t his and is surprised to learn he plans to take the surviving twin home and set up a nursery for him. Graham tells Submit that, after his parents died, between the ages on nine and eleven, he lived in nine different houses before finally ending up at Motmarche with Henry. Graham tells her that taking in one sickly baby won’t be too much trouble, then delivers one of the most devastating lines of the book:

Well, Submit thought. What a confusing and circuitous brand of compassion he possessed, and for a baby who wasn’t his, whose mother had sued him, clipped him for a good bit of money, then jumped out a window. She opened her mouth, thinking she could find words that would sort all this out and make logical sense.

Then he summed it up better than any logic could have. “What an unspeakable mess life can be,” he said. (emphasis mine)

Graham continues to visit Submit at Morrow Fields, stopping by on his way to and from London. During one visit, he tells her about studying theology (Henry was an atheist). She tells him about going to Cambridge with Henry while he taught and how some of the students developed infatuations with her. Over the course of the summer, they reveal more of themselves to one another:

he had a way of stopping leaving long, interested silences that made her want to fill them in with honest, meaningful words. By the end of July, she’d told him of her father, her schooling, her marriage; she’d discussed the death of her mother. The inn at Morrow Fields seemed to be a private world where one could share such things.

III. chapter twenty-three (the clothesline)

Submit is hanging her laundry on a clothesline when Graham comes to visit. The sun is bright, there is a light breeze:

He watched her rise through these shadows as she stood, watched the clothes wrap around her and hit her in the face. Graham too felt wrapped – rapt. He was caught up instantly in the private watching of her, in the guilty pleasure of scrutiny without observation. He stood transfixed.

Submit is not wearing hoops under her skirts today, the fabric of her dress is pulled back to keep out of her way. The buttons along her wrists and forearms and down her neck were undone. Graham has not seen Submit this way before. Preoccupied with her laundry, she startles when he approaches her. They smile and laugh, both happy to see each other again. Graham helps Submit hang her laundry.

They talk again about their background, Submit shares that hanging her own laundry is not embarrassing; before her father became a successful abattoir, she witnessed her mother perform all the domestic work in their home (and then waste away once her father hired servants to do this work for her). Graham helps her carry her things back to the inn. Graham notices Submit is struggling to button her sleeve, he takes hold of her arm in order to help her:

He could feel her pulse beating through her arm, beneath his hand. His own heart began to thud. He wanted to bring her arm up around his neck, bend his nose to it, feel the skin against his mouth, breathe in its smell, kiss it, lick it, bite it –

Graham embraces Submit and attempts to kiss her again but she rebuffs his advances. They argue over their shared desire – Graham wants to explore the desire physically, Submit knows this is a bad idea and can’t help but laugh over the situation. She tells Graham that she likes him – is flattered that he would make a move on her – but she is not interested in a “tangle” with him. Graham sulks and they argue about Henry, again:

“You don’t want to make love to me – as Henry did so very nicely, I might mention. You want to cuckold Henry Channing-Downes.” Submit thought she had tied all this up for him rather neatly.

But he laughed. “You’re bloody right, I would like to have cuckolded Henry. But Henry, my dear, is dead –“

“Not in your mind he’s not.”

Graham storms off on his horse. In the next chapter, they write impersonal letters to each other, apologizing for how their last meeting at Morrow Fields ended.

math fixed point(s)

The phrase “fixed point” appears twice in Black Silk. In mathematics, “a fixed point is a value that does not change under a given transformation. Specifically, for functions, a fixed point is an element that is mapped to itself by the function.”22

It was not until this seventh reading of Black Silk that I realized “fixed point” might be referring to something . . . mathematical? Cuevas has two math degrees: an undergraduate degree in applied mathematics and a graduate degree in theoretical mathematics, she explained in an All About Romance interview, “I’m sort of in both camps mathematically speaking.”22 During this reread of Cuevas’s backlist I have tried to be more aware of the “math vibes” but I am a college drop-out, like, fifteen credits shy of bachelor’s degree in history; I had to take algebra I three times. Forgive me for not making the connection sooner.

I. Submit

The first use of “fixed point” appears in Part I, chapter six – Graham is at the rented estate of his mistress, Rosalyn, for his thirty-eighth birthday party. Submit has been trying to find Graham all evening. She is supposed to deliver to him a box that was bequeathed to him in Henry’s will. The will stipulated Submit should present this box to Graham. (The box. The Box.)

Inside the box are the twelve drawings that led to Graham’s expulsion from school.24 Submit, curious about what could be so special about this box, opened it and looked inside; she saw the erotic drawings. Under the guise of following Henry’s will by hand-delivering the box to Graham, she would like him to explain to her uh, what the fuck her dead husband was doing with a box of intricately rendered pornographic drawings and why he wanted Graham to have this box.25

Prior to this moment, Graham and Submit had never met – she is only familiar with his name and that he is Henry’s cousin. We learn that a few years before the start of the book, Graham had taken ill and Henry went to visit him; he insisted Submit remain at home.26

Graham and Submit’s exchange during their first meeting is electric; the box of erotic drawings between them – Submit wants Graham to tell her what he knows about the box and its contents (even though she already knows what is in the box). They argue over who will take the box then Rosalyn, Graham’s mistress, joins them; she is also curious about this mysterious black box. At one point, all three have their hands on the box at once before Graham is able to pull it away and hide it behind his back (Rosalyn does try grabbing for it again).

Rosalyn asks Submit to stay with her at the rented home instead of going to the posting house. Submit has somehow repossessed the box in the commotion of introductions. Everyone and everything is in flux except Graham and Submit who remain static:

A crisp gale swirled rain in, lifting all the ladies’ skirts about. Chaos. Submit Channing-Downes stood motionless in this, one hand held against her skirt, the other arm loosely wrapped around the retrieved box. She was faced away from Graham in profile, steady against the wind, the only fixed point in the commotion besides himself.

It suddenly dawns on Graham that the little widow Submit knows what is inside the box.

II. Margaret

The second instance of “fixed point” comes much later, in Part II, chapter thirty. We are with Graham as he remembers Margaret, an upstairs servant who came to work for him for a short while before she married a local farmer:

In the Dark, Graham began to think of the serial. Affair after affair, all snide, all exaggerated, all true. And Margaret. [ . . .] Lord, he had forgotten about her. Which was a shame, because there seemed within Margaret a clue. Something about himself he had forgotten, lost sight of, something good . . .

The other servants would call her Peg due to her limp. Margaret has placed a vase with flowers on Graham’s dresser. No one had thought to display flowers in this vase before and it pleased Graham to see it being used in this way, “it looked different with all the color. The flowers, in order to be small enough to balance the few inches of the vase, were semiweeds. Wild violets, Sweet Alison, Welsh poppies, others, a bit of green. One would have to walk a long way to make such a fine collection.”

At the end of the summer season, Graham has taken quite ill. Under doctor’s orders, he spends a week in bed;27 Margaret appoints herself his nursemaid. Graham and Margaret talk as she helps cares for him; he learns that although she is pleased to be marrying soon, something seems to unsettle her about her upcoming nuptials.

After his convalescence, Graham suggests to Margaret that she come with the house staff to London for a short while. Once they are settled in London, Graham and Margaret begin sleeping together. Their affair ends, amicably, once he moved to Bath and she went back to Netham. For her wedding, Graham sends her a punch bowl and cups. He also sends the, “small vase with its Etruscan lines,” the one she filled with wild flowers and placed on his dresser. The last time he sees Margaret, she came in person to thank him for the wedding gift and the vase.

The vase returns to Graham – Jim, Margaret’s husband, donated several of her things to the local church after she died in her sleep; Graham bought the vase in the church sale. The memory of Margaret passes over Graham and he thinks:

People missed things. People didn’t notice; people didn’t care. People’s own misperceptions made black into white, made grey into whatever they wanted it to be. Graham began to think it was all fiction. Life was much less fixed than people imagined it to be. Then the thought of Margaret brought him back. She was a fixed point, someone he felt he had known, though briefly, truly well.

a different sum

The phrase “fixed point” does not appear in Part III, chapter 36, however this math reference is such a smart turn of phrase I wanted to include it. Graham and Submit have finally reunited after months apart. They have spent several hours making love in Henry’s bed, which, I will concede, is a little weird out of context. But in context, which is what matters in romance, I think most readers will understand why it is necessary Graham and Submit come back together here.

This is not a supernatural romance, yet the metaphorical ghost of Henry haunts almost every page of the book and the characters. He is always appearing – in their memories, in their mannerisms, that goddamned box, the will. This presence is a burden for Graham but it’s more complicated for Submit who loved her husband very much. She says, “her marriage to him had been the most healing, salutary event in her life.” Their age difference – she was a young teen when they married, he was in his fifties – did not matter to her, but it did to Henry, who in spite of himself, returns her love.

Graham wakes before Submit and looks around Henry’s bedroom, noticing the changes to the space and what has remained the same. He sends for hot water then uses Henry’s razor to shave:

They read the same books, though siding with different authors. And then there was the enigma of their strong attraction to the same woman.Wonderful, mysterious Submit. Like her vocabulary, he supposed, little syllables of Henry’s life had worked their way into him until they were indistinguishable – inextirpable – from himself.

He caught himself staring at the face in the mirror. In that moment, it was the twisted, serious mouth of a man trying to shave his jawbone without taking off his ear. Though even relaxed, it was not the face of a happy man.

Henry had not been happy, Graham knew, at least not when Graham had known him best. Then later with Submit, Graham suspected, Henry wore his happiness like a torment, afraid of losing it – to a younger man, to the frustration of a diminishing life span. To a sense of having found happiness too late or of not deserving it. To the worry of stealing his happiness from Submit’s storehouse. To the guilt over making a realist out of a romantic young girl.

Graham wanted to make Submit a romantic again. And he would like to be happy. All his life, it has been perhaps simply this: Not wanting to be different from Henry so much as wanting all he had in common with Henry to total a different sum – a happy existence. (emphasis mine)

Graham cannot reconcile with Henry. Submit will always love Henry. Life is devastating and complicated, beautiful and weird.

miscellany – I have already written too much

bureaucracy, paperwork:

- Henry’s will

- Graham’s paternity suit

- Pandetti’s Box

- The Rake of Ronmoor

- Rosalyn’s divorce

references Black Silk in Cuevas/Ivory’s later work:27

- Sleeping Beauty – Lady Motmarche mentioned.

- The Indiscretion – The main characters attend a state party hosted at Motmarche; appearances by Submit & Graham.

- Untie My Heart – a man referred to as Motmarche is mentioned as someone who knows about art and insurance.

(I am writing a stand-alone post about pornography, art, and my relationship with Black Silk. I hope to finish it someday.)

- I love this post by Sanjana! I am inspired to write about the things I love (or dislike lol). It is gross and exhilarating to share how much something means to me, that during the reading of (watching, listening to) this thing has changed me. ↩︎

- Starlit Surrender is the apt title iykyk ↩︎

- Evangeline has slept with Adrien. She did not, however, ever become pregnant by him. ↩︎

- I love it even though Christina makes a “let them eat cake” reference. ↩︎

- I really like The Proposition – it’s funny and sexy but it’s not better than Black Silk, not in this world! ↩︎

- Sometimes readers say “rake” when they mean “person who fucks a lot.” Fucking is value-neutral! ↩︎

- “It was an English divorce, Christina. My wife was a French Catholic. In France, I am still married to her.”

(It’s a French/Catholic thing! there is a similar situation in Bliss.) ↩︎ - I am not proud to have left a reactionary comment on a popular romance website’s (negative) review of this book lol people are allowed to not like things but invoking tstl is rude 🔪 ↩︎

- He called to her, “it’s just, counting from June–“

“Mid-May.” Christina came into view. He imagined she smiled as she sat on the bed. “My last flow was mid-May. Three years with Richard and not a whisper. With you, I’m so fertile, just moving into the same house and I never see blood again.” ↩︎ - I think Emma coined this phrase during a Reformed Rakes episode see also: Hot Girl Hobby, another useful term coined by Emma. ↩︎

- When I borrowed Black Silk from the library in March 2023, I was not expecting to read what has become my favorite book. It’s kind of exciting, isn’t it? That your next favorite book is waiting to make itself known to you. I read it last a few weeks after the 2024 election when I was unable to concentrate on anything; I was in need of a re-read. I chronicled this re-read/breakdown on Bluesky (in addition 40 pages of handwritten notes in my reading journal, have I mentioned I am a loser?) ↩︎

- Graham is widowed; his young wife, Elyse, died during childbirth. He is a Gemini. ↩︎

- This is an oversimplification of their dynamic for the sake of this post is already too fucking long. Black Silk is queer, idc idc, specifically because of (but not limited to) Graham and Henry’s relationship – Graham is kicked out of his home and disinherited because, in Henry’s eyes, and in the opinion of the courts, his sexuality is dangerous, capable of corrupting the public. He is taken in by his theater friends, he becomes an actor to support himself; the relationship with Henry is never reconciled, something that is painful even if is clear reconciliation was never possible. ↩︎

- imo this is unearned! he sleeps with a lot of people, drinks champagne for breakfast, and smokes cigars while having a bath – what’s the big deal? ↩︎

- Brandon Taylor has written a series about story basics. His post about scenes is great:

“the essential element of a scene, the thing that makes it a scene, is the time signature. That is, it must unfold in the time of incident. But what must unfold. Usually, actions and events. Dialogue. Changes in the material reality of the setting.”

“a scene happens in a place. It involves people. Doing and saying things—saying nothing counts as saying something for our purposes—and sometimes even thinking things. But a scene may also contain a flashback or a memory. It may interrupt itself to digress. It may do any or all of those things. But as long as the time that dominates is the time of incident, it’s still a scene.”

https://blgtylr.substack.com/p/story-basics-3-scenes ↩︎ - I had to ask myself if time in metaphysical even though I already assumed it was. I also read this post: The Three Metaphysics of Time – Thinking About Thinking ↩︎

- I’m always thinking about The Black Joke as liminal space, from Tom and Sharon Curtis’s The Windflower (not the physical ship but the time on the ship. ↩︎

- I empathize with Arabella. The text is clear that the proceedings were humiliating for both Graham and her. ↩︎

- “the final period at the end of his ride,” see fixed point below. ↩︎

- Several POV changes in these chapters. In my reading journal I wrote, “POV shifts quickly here, pay attention! Graham, Submit, Graham, Submit, Graham . . . ” ↩︎

- See fixed point below. ↩︎

- Fixed point (mathematics) – Wikipedia ↩︎

- All About Romance: Interview with Judith Ivory aka Judy Cuevas ↩︎

- The box containing the drawings is called Pandetti’s Box, after the artist who drew them. Part I of Black Silk is also called Pandetti’s Box. The epigraph for Part I:

Being heretofore drown’d in security,

You know not how to live, nor how to die;

But I have an object that shall startle you,

And make you know whither you are going.

John Webster

The Devil’s Law Case

V, iv, 109-112 ↩︎ - Submit does not yet know Graham is a subject in the drawings. ↩︎

- This passage is so revealing about Henry but I did not have the time or patience to properly work it into the section about math and fixed points. But people should read it anyway:

“Do you know,” she reflected, “the one time in twelve years of marriage that Henry did go to visit this cousin, he refused to take me along. It was the only time we were separated. And the night he left, our roles reversed themselves so peculiarly, as if he were the child—with clubhouse secrets he was dying to tell, but didn’t dare share.” ↩︎ - I think this is the same timeframe, referenced earlier, when Henry visits a sick Graham. ↩︎

- not Black Silk-related but Judy Cuevas-related – Sherry Thomas references Cuevas throughout her romances:

* most obvious Beguiling the Beauty, Thomas’s homage to Ivory/Cuevas’s Beast.

* Thomas references Marie du Gard’s father (Bliss & Dance) in Delicious:

He did not even require the third course, the petit pot de crème au chocolat that the year before had had Monsieur du Gard, the Parisian industrialist, weep openly at the table because it made him remember his chocolate-loving sister, who’d given up school—and chocolate—so he could be educated.

* Thomas references Mick from The Proposition in His at Night:

In the morning everyone drove over to Woodley Manor for a look at the disgusting mountain of dead rats. The rat catcher, with his exhausted rat dogs, a triumphant ferret, and an incomprehensible accent, proudly twirled his dark, luxuriant mustache as he posed for Lord Frederick’s camera, commemorating the occasion. ↩︎