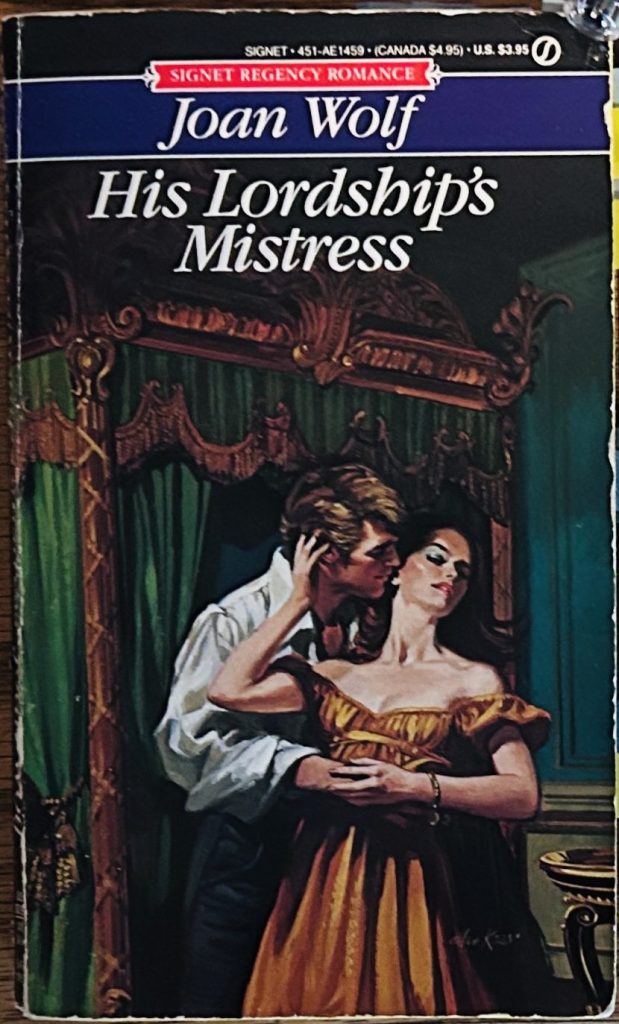

Earlier this year, I was a guest on The Reformed Rakes podcast (!!!) where I spoke with Beth and Emma about His Lordship’s Mistress, by Joan Wolf. You can listen to that episode here.

This post is a continuation of my mistress character in historical romance project. I will be writing more about books we discussed during the podcast – His Lordship’s Mistress and The Scandal of Rose by Joanna Shupe, with references to Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights by Molly Smith and Juno Mac.

His Lordship’s Mistress, by Joan Wolf, 1982, Signet

characters: Jessica Andover and Phillip Romney, Earl of Linton

We begin His Lordship’s Mistress learning that Jessica’s stepfather has died and has run up debts against the family’s estate; her mother passed away years ago, off page. Jessica has two younger brothers to raise and a horse farm she is desperate to hold onto; she makes an arrangement with a family friend who will lend her money and hold the estate title for her as she pays him back over time. When this family friend suddenly dies, his heir – who wants the land – threatens to call in the mortgage if Jessica doesn’t either pay up or marry him. To save the estate, and prevent having to marry the blackmailing heir, Jessica heads to London, takes out a high-interest loan to pay off the evil heir, and becomes a stage actress. She hopes her stage presence will lure a wealthy protector so she can become his mistress. Jessica believes that by becoming a rich man’s mistress she will earn enough money for her family to stay together and keep the horse farm.

Philip Romney, Earl of Linton, spends most of his time at his country estate – managing the estate and the farmers. While making his yearly visit to London, Philip’s friends lure him to the theater with news of a beautiful, new star – Jessica. Of course, he is instantly charmed by her during her performance and meets her after the show. Philip hasn’t taken a mistress in a while and is so enamored with Jessica he asks her to become his mistress; they agree to terms.

This is a romance, so of course Philip and Jessica fall in love; however, Wolf makes some notable choices in this 1982 release. I have read a handful of recent releases that struggle to engage with the politics or labor of sex work1 – often excluding the portrayal of the sex worker character doing their job on page.

Jessica’s relationship with sex work is straight forward – she understands this is the thing that will most efficiently get her the money she needs to provide for her family and ensure family’s estate is not sold. Wolf does not go to lengths to write around what Jessica feels she must to do make money:

If anyone two years ago had told her she would consider becoming some rich man’s mistress she would have stared incredulously. But in her present situation she didn’t see any other way out. The world would condemn such a course of action, she knew. But then she had no intention of letting her world know what she had done. And Jessica, who had highly ethical but unusual standards, found the idea less distasteful than swearing to love, honor, and obey someone she hated and despised.

The day of their first tryst, Jessica realizes she is ill-prepared for what to expect or how to act as a mistress. Before meeting Philip at their townhouse, Jessica seeks advice from fellow stage actress Eliza Bereton, “one of Covent Garden’s staple character actresses, was well equipped to advise Jessica. In her youth she had enjoyed the favors of some of the town’s most notable men and she now resided in a comfortable, well-furnished house that was the fruit of her labors.” The author’s choice of the word “labors” here indicates Mrs. Brereton’s sex work and her work as an actress made it possible to not only survive, but thrive. Although her appearance in this romance is brief, I see Jessica’s arc mirroring Mrs. Brereton’s – some people did sex work for money or gifts in order to survive and their lives were not terrible because of this choice.

Eliza is godsend – she takes Jessica to find the appropriate clothing befitting the mistress of a wealthy earl, suggests a method to prevent pregnancy; and, most importantly, vouches for Philip’s character as a provider, aiding in the vetting process which helps Jessica know that he is a safe choice. I noted Jessica does not think of Eliza as a “fallen woman” rather, she regards Eliza as a colleague and resource, valuing her experience and perspective:

Jessica had been frank with her, and Mrs. Brereton had been impressed. “Linton is quite a catch, my dear,” she told Jessica admiringly, and, when the terms of the agreement had been disclosed, her eyes had widened. “He is being extremely generous.” She had looked thoughtfully at Jessica. “You are not at all the usual thing, my dear.”

“I am not the usual thing, Mrs. Brereton,” Jessica had replied honestly. “That is why I am here.” She met the other woman’s gaze directly. “I haven’t the vaguest idea of how I should behave and I hoped you would not be offend if I asked you to advise me.”

labor and/or love

During the podcast, Emma said something2 that I think about a lot since our recording . . . so many of these books about mistresses want the salacity that comes with writing a sex worker while failing to consider sex work as a business. I believe there is a misconception that sex work is all about sex acts, ignoring the labor that goes into attracting and sustaining clients: there are the endless administrative duties, often without the help of an assistant. This is why romances that avoid engaging thoughtfully with how sex workers earn money read hollow at best or dehumanizing and insulting at worst.

His Lordship’s Mistress is interested in Jessica’s work as Philip’s mistress: she is his companion in multiple areas of his life. They spend a significant amount of time together in public spaces – with his friends, where she is careful to evaluate the manner in which she presents herself to Philip and his friends:

Jessica hesitated, her eyes going to Linton. He met her gaze and realized she was looking to him for guidance. [… ] She would see what he would do — so their briefly locking eyes had told him — and she would act accordingly.

The intimacy between these two as lovers and friends naturally develops over their relationship: Philip helps her read lines in preparation for her performances. He drives her to the theater in his carriage and is present most nights to watch her perform. When they are alone, they have discussions about art and politics, exchanging ideas. This companionship is part of Jessica’s work as Philip’s mistress, even though they are falling in love.3

Wolf does not attempt to rework the romance between Jessica and Philip as a to obfuscate that Jessica earned money to pay off her mortgage by becoming his mistress. Instead, at the end of the book, we switch POVs to Jessica’s governess, Miss Burnley, who learned what Jessica decided she had to do to save the family home and farm,

It had sounded sordid, Jessica’s revelation to Miss Burnley this afternoon. But who was she to judge Jessica, Miss Burnley thought now humbly, as she gazed fixedly at her peas. The very food on her plate, the roof over her head, were there because of Jessica. She had never had to make the kind of decision Jessica had. She had always been protected by the very girl whose conduct she had been silently condemning.

Something else Emma mentioned in the episode helped me to reframe how I view Jessica’s decision to leave her family’s horse farm to her brother instead of finding a way to continue to manage it. Because Jessica was able to pay off her mortgage and focus on setting the farm up to become a profitable stud business, she has made it possible for her brothers to run a successful horse breeding farm and they will be able to live independently. I had not considered this angle. Jessica giving up the horse farm is not a move of self-sacrifice, this is what she has always wanted: to keep her family together and provide the best future for her brothers.

When I first read His Lordship’s Mistress I struggled with Jessica’s decision to give Winchcombe to her brother because I thought she should want more for herself (kind of embarrassing to write this out). I was holding Jessica to an unfair standard. Also, I didn’t notice until I reread the book for the podcast, but Philip actually asks Jessica what she would like to do with the horse farm, he doesn’t assume she would want to give it up when they marry:

“What do you want to do about Winchcombe?”

There was silence as she sat thinking, then he felt her hand stiffen in his. “Philip,” she said excitedly, “I’ll give Winchcome to Geoffrey!”

He kept his eyes on her hand. “Are you sure?”

reading is political*

*sometimes the politics in books are spineless

The Scandal of Rose (2024) by Joanna Shupe is set during the Gilded Age and is about Rose, a nineteen year-old actress from Ohio and Alfred Moore Emerson III (Moore) a divorced thirty-eight year-old business tycoon living in New York City. Rose moved to New York City to pursue her dream of becoming a stage actress. She was escaping scandal, too: back in Ohio, Rose had sex with a man she had been seeing who promised to marry her. This man never intended to marry Rose; instead, he spread rumors of their tryst. Due to this traumatic experience, Rose swore to keep liaisons with men, “casual and sleep with a man only once, no matter what,” (unless the sex happens during marriage).5

Moore has a scandalous past of his own: he divorced his first wife years ago and in order to expedite the divorce proceedings, he hired a chorus girl to lie about having an affair with him.6 The press went wild for this and Moore believes the scandal upset his father so much that his father died of a heart attack.7

Since his divorce, and the death of his father, Moore has been living respectably and without any new scandals. He takes an interest in Rose, frequenting her performances at the theater. One evening, after a show, Rose follows him out and flirts with him. He thinks he’s too old (and divorced) for her and she assumes he’s interested in paying for a companion:

Was Moore searching for a mistress? If so, I needed to set him straight. Many actresses I knew had benefactors – men who paid for their lodgings and lifestyle in exchange for intimacies. I never judged them8 [ . . . ] yet I wasn’t interested in a benefactor. I had dreams of financial freedom, one that depended on no man. One that couldn’t be taken away or leveraged. One that was all mine. Only when I was financially secure would I choose a husband and move out to a big house in New Jersey or Connecticut. I’d grow flowers and have children and all the happiness in the world.

There are a lot of assumptions Rose has about these women who are “selling intimacies”: such as that these women getting paid for sex are incapable of distinguishing the difference between having sex with a man for money or being in a relationship with a man. It also does not consider that these women had their own financial freedom! She repeats throughout the book that her goal of financial independence does not include depending on a man (her boss at the theater is a man but that’s different; it’s, you know, legitimate work).

What has left me confused is how Rose thinks about all the one-night-stands she’s had and how they were not sexually satisfying. I am unsure if this is supposed to signal that, of course, sleeping around is unsatisfying? That good sex only happens when you are in a monogamous, long-term relationship? This reminded me of something Molly Smith and Juno Mac wrote about in Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights,

“having sex – too much or the wrong kind or with the wrong person or for the wrong reason – brings about some kind of loss.” sex is too intimate . . . too special to be sold. Implicit in this view is the sense that sex is a volatile substance for women and must be controlled or legitimized by an emotional connection.

As I wrote earlier, my issue with The Scandal of Rose, and romances like it, is the separation of work from sex work. It is important to Rose that lines are drawn between acceptable labor and unacceptable labor – lines that do not make any sense to me in a book about a mistress (who is also not really a mistress)! Rose has such a narrow idea of what independence from men means. She never asks for advice from the actresses she works with, women who are more experienced and resourceful than Rose. She doesn’t use the money or gifts Moore gives her to realize her goals; financial independence is a vague idea other than no man can be part of it. And I actually struggle to decipher if Rose became Moore’s mistress or not because the text is so muddled:

“I only sleep with men for fun, not profit. Take it or leave it.”

“So I may give you gifts and trinkets.” I gestured to the necklace. “But nothing substantial. Do I have it right?”

She began unpinning her hair with ruthless, frustrated movements. “No . . . yes . . . I don’t know! This is a lot for me to take in.” [ . . . ] “I don’t want to be a mistress. Men use sex to control women9, to take away our choices. They make promises and then change their minds, leaving us to pick up the pieces.”

Moore buys Rose a townhouse – with her name on the deed, yet Rose holds strong to her rule of sleeping with a man only once, “There is no arrangement, you daft man. We are fucking only once -today-and that’s all. I’m not accepting the gift of an Upper East Side townhouse!.” Rose does decide to remain in the house when Moore changes tactics; the house is not a payment for sex rather he bought it for her so Rose would have a safe place to live:

“Allow me to give you this. It’s a good house on a good street. You won’t need to worry over your safety [ . . . ] I don’t wish to worry over your safety. I’ll sleep better knowing you are here.”

I have read this kind of muddled politic from Shupe before;10 in her 2019 release, The Prince of Broadway, Clayton “Clay” Madden, the owner of New York City’s most exclusive gambling club has a strict “no women allowed” policy that extends to sex workers. Florence Greene is a young woman from a wealthy family who wants to open a gambling club for women. She sneaks into Clay’s establishment for research, he notices her in his club but has not yet confronted her about the “no women” policy:

“[h]ard to say why Clay allowed her entry. After all, the Bronze House had strict rules for gaining entrance. Men of a certain class congregated here, men with deep pockets and little sense. Women were forbidden, per his explicit order. He didn’t even permit prostitutes here, as many casinos did.”

[ . . . ] “Annabelle Gallagher. One of Clay’s few friends and investors. She owned the brothel next door to the House, providing a service to the fancy fat cats that Clay was unwilling to undertake himself. He did not peddle in flesh, though Anna’s girls were willing and well cared for. It was her business, one he did not judge.” 11

Similarly, in Lisa Kleypas’s 2004 release, Devil in Winter, Sebastian St. Vincent takes over the day-to-day running the gambling establishment of his father-in-law. One of his first acts in this role of management is to fire all of the sex workers who lived and worked out of the gaming hell. His reasoning: “While I have no moral aversion to the concept of prostitution — in fact, I’m all for it — I’m damned if I’ll become known as a pimp.”

Ten years prior to the publication of Devil in Winter, Kleypas released Dreaming of You featuring Derek Craven, another gambling hell owner. But Craven has a different policy regarding sex workers living and working at his club:

“He takes no profit from them, Miss Fielding. Their presence adds to the ambiance of the club, and as an added enticement to the patrons. All the money the house wenches make is theirs to keep. Mr. Craven also offers them protection, rent-free rooms, and a far better clientele than they’re likely to find on the streets.”12

a conclusion

Sex work is a labor issue and divorcing sex work from labor – even in a romance – is dehumanizing. The Scandal of Rose is an example of the decreasing emphasis on sex work as WORK – something that many people (past, present, future) choose to do for a variety of reasons – like to financially support themselves and their families.

In His Lordship’s Mistress, Philip pays Jessica for her labor as his mistress. Yes, they fall in love during their time together and Jessica struggles with how to process their developing intimacy, but the author does not attempt to distinguish what Jessica chose to do from sex work. Jessica would rather earn money by becoming a mistress than marry a man she hates who is black-mailing her. The publishing date of His Lordship’s Mistress, 1982, stands out because there is more empathy for someone in Jessica’s situation – and is making clearer ties to sex work – than some recent releases.

coming soon – Mary Balogh’s Tempting Harriet, the Judy Cuevas/Judith Ivory re-read, War & Peace: a six month update

further reading and watching

Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights (2018) by Molly Smith and Juno Mac– shout out to Emma for frequently mentioning this book written and – very importantly – endorsed by sex workers.

No To A Nordic New York from 2023 but still relevant:

Decriminalization means removing the criminal penalties around the buying and selling of sex and sexual services. It does not mean reducing penalties for abuse, trafficking or exploitation. That is something I cannot stress enough; decriminalizing sex work does not decriminalize trafficking, abuse or exploitation. Sex workers don’t deserve to be criminalized or face harm, but neither do our clients or third parties such as drivers, managers or landlords assisting us to work safely.

Debunking the Entrapment Model, a.k.a. the End Demand Model:

The Entrapment Model incentivizes landlords and financial institutions to discriminate against sex workers, creating barriers to obtaining secure housing, buying property, or accessing financial services. For example, Norway’s “Operation Homeless” initiative was designed to have sex workers evicted from their homes. Between 2007 and 2014, at least 400 sex workers were evicted, most of whom were migrant women.

Holly Randall Unfiltered – Kaytlin Bailey: The History and Future of Sex Workers – this interview is great because Bailey spends time talking about how sex workers view and talk about their history; I think about it a lot because of how romancelandia often positions itself as inherently feminist or sex positive while doing a lot of heavy lifting for SWERFs, TERFs, and anti-sex prudes. Bailey also explains the difference between decriminalization and legalization, two frameworks that have vastly different outcomes for sex workers:

decriminalization: stops the arrests, sex work is not a crime – buying or selling, no new bureaucratic systems.

legalization: would establish bureaucracy, creating a new legal structure through which to govern sex work.

similar to what Bailey talked about in the above referenced video, this instagram post discusses modern perceptions of the lives of 19th century courtesans.

Working Girls (1986) directed by Lizzie Borden – we spend a the day in the life of artist and sex worker Molly. She works in a brothel with other women and has a shitty boss. It’s not unlike other kinds of jobs – it’s kind of boring and monotonous, Molly is guilt-tripped into a double-shift, she goes on a convenience store run for everyone, helps train a new colleague . . . all shit people with jobs do.

Thief (1981) directed by Michael Mann – Thief is not directly connected to sex work but it is about labor and the politics of who profits from your body’s labor.

- If the excuse for these politically toothless books is that you don’t want to read or write main characters having sex with people that are not the other main character or about people who are paid for sex or pay for sex . . . why are you reading or writing a romance about sex workers? ↩︎

- “I think that’s one of the things that Jessica gets at, where it’s like she knows that she is different in front of people who are potential clients than she is not with that. But in practice, the idea of only sleeping with anyone once makes no sense. Sex work is a business with clients. Getting new clients is the most expensive part of any business, especially in sex work, where you’re vulnerable to violence. It makes sense to develop consistent relationships with vetted clients. I just think of the author’s write characteristics of this way. It’s obvious that they’re using sex work as a way to add salacity to their books. Like, Oh, this is dramatic or sinister or it’s sexy, rather than thinking about sex work as work and as a business. What other business would only sell to one client one time? It doesn’t make any sense. It’s just one of those things that I think betrays a lack of thought in how this is integrated into the books.”

Reformed Rakes Podcast ↩︎ - “Can you buy love? It’s complicated” by Jessie Sage: “The fact that our relationship is transactional is a feature, not a bug: it is the very condition for the possibility of the type of intimacy that can occur between providers and their special clients. Just because a relationship has bounds doesn’t mean that it’s fake. [ . . . ] These relationships are transactional; they can also be deeply meaningful.” ↩︎

- Linking ethics with aesthetics rather than labor practices is the problem! From Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights (2018) by Molly Smith and Juno Mac:

As Melissa Gria Grant writes, “An image of a woman in porn can be seen to stand in for ‘all women,” whereas an actual woman performing in porn is understood as essentially other. So ‘defending women from images of women in porn’ is a project that’s understood (by some feminists) as a broader political project, whereas the labor rights of women who perform in porn are considered marginal. ↩︎ - When Rose says, “sleep with” she means penetrative sex, hand and mouth stuff does not count. Rose and Moore have multiple sexual encounters in the book and although Rose will only sleep with a man once, she makes this distinction between sex and foreplay to extend their relationship. After their first sexual encounter, Moore goes down on Rose but he refuses to allow her to reciprocate,

“Does this not count, then?” He tilted his chin toward the desk.

“No. This was a . . . an overture. Neither of us removed our clothing. Your intimate parts never met with my intimate parts.”

Maybe this is Shupe’s attempt at subverting the romance trope where a man professes to only sleep with a woman once before moving on. It does feel a little silly, though. ↩︎ - The chorus girl is never given a name in the text and we never spend any time considering how her reputation was affected by the public scandal. ↩︎

- Moore’s father was actually was found dead, in bed with his mistress. ↩︎

From Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights (2018) by Molly Smith and Juno Mac:

Rather than focusing on the ‘work of sex work’ both pro-sex feminists and anti-prostitution feminists concerned themselves with sex as symbol. Both groups questioned what the existence of the sex industry implied for their own positions as women; both groups prioritized these questions over what material improvements could be made in the lives of the sex workers in their communities. Stuck in the domain of sex and whether it is “good” or bad”bad” for women (and adamant that it could only be one or the other) it was all too easy for feminists to think of The Prostitute only in terms of what she represented to them. They claimed ownership of sex worker experiences in order to make sense of their own. ↩︎- From Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights (2018) by Molly Smith and Juno Mac:

In an article about brothel work in Germany, journalist Sarah Ditum [ . . . ] writes, “Prostitution [ is ] an institution that insists on the dehuminization of women, the grinding away our souls so we become easier to fuck, use, kill.”

The use of ‘we’ and ‘our’ suggest that the experiences of a sex worker [ . . . ] are a struggle shared with all women. (Of course, the same cannot be said in reverse; ‘women’s liberation’ is not always shared with prostitutes.) ↩︎ - This post has been updated to include this sentence; it was left out of the original posting by mistake. ↩︎

- Something I have noticed in romance novels is the pervasive, dehumanizing idea that sex exchanged for cash (or goods) is considered an inferior experience or that it does not count as “real” sex. From Shupe’s The Prince of Broadway (2019):

Anna tossed back the remaining liquid in her glass. “I’d best return next door.” She rose. “Shall I send over a nice young woman to keep you company tonight?”

He thought about it. The problem was Anna’s people were being paid. Clay didn’t like feigned passion. And he knew his face wasn’t the kind to draw admirers. “No, that’s not necessary.”

—–

Another instance from Kristen Callihan’s 2012 paranormal historical romance Firelight:

“A rather pathetic imitation for the real thing.” And later:

“Eavesdropping give you a cheap thrill? I’d have to guess you’re still repressed by that juvenile fear of bedding whores.”

“Is that what you call it?” Archer flashed his teeth. “Here I thought it was an aversion to paying someone to want me. I’ll get my pleasure for free, thanks.”

—–

Authors will use a kind of short-hand where the person with an “aversion” to paying for sex (or someone who avoids an association with sex work/ers) is good and the person paying for sex is antagonistic.

↩︎ - Although Sara Fielding, Craven’s love interest, is sympathetic to sex workers (having written a popular book, Mathilda, about a sex worker) she does not support the enterprise, “After the research she had done for Mathilda, she was very much against the practice of prostitution. She had sympathy for the women who were enslaved by such a system.”

I don’t think Kleypas’s politics with regard to sex work are similar to Sara Fielding’s, I think they might be meaner. Romance authors using and skewing the histories of sex workers to fit into a carceral feminist fantasyland is not new nor is it a thing that was done “in the past”. ↩︎